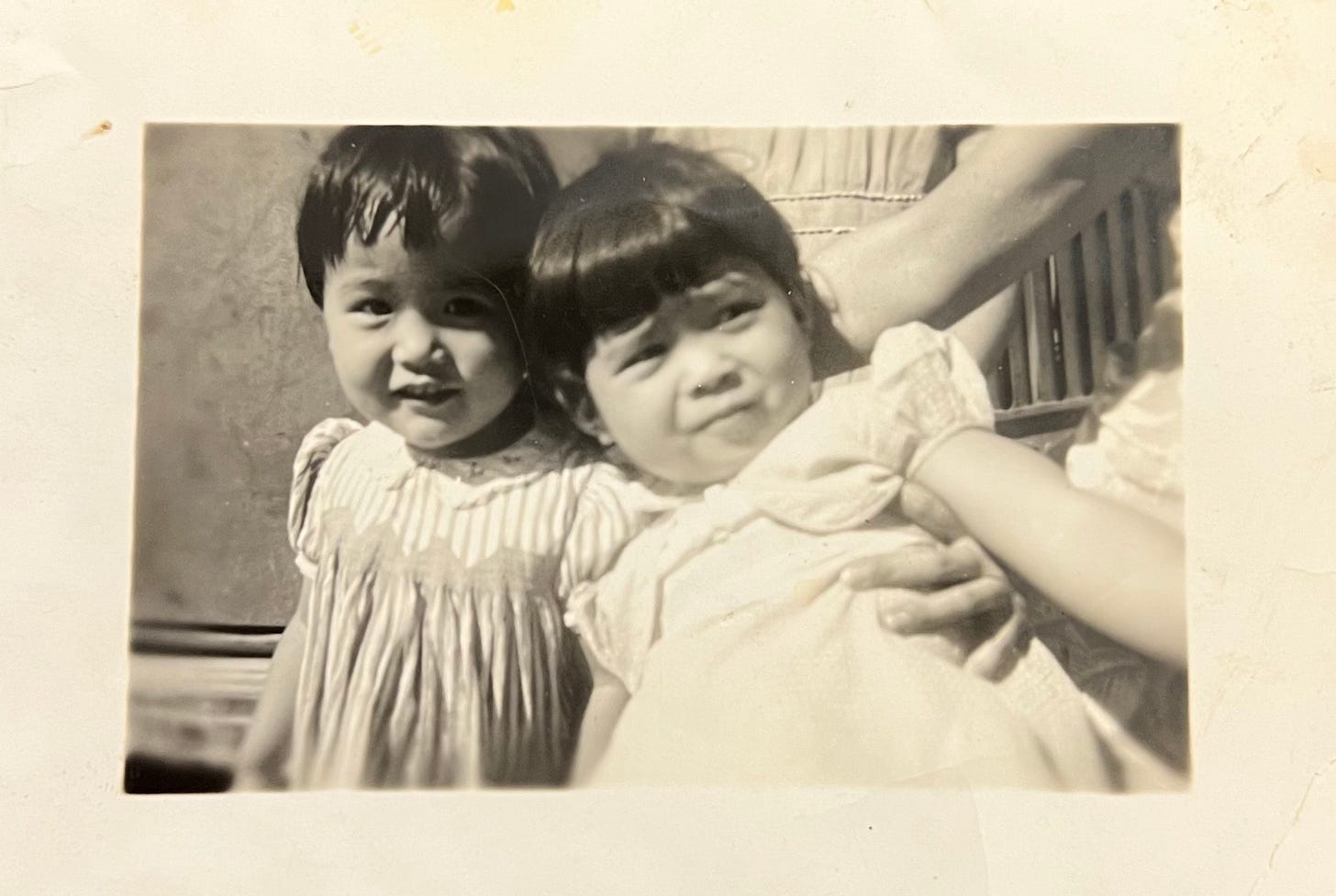

(me between Yuriko aka Yuyu to my left and Viola Masako on my right)

Last month, I lost someone who will forever mean the world to me.

I met Viola Masako Nakamura Lam, known as ‘Vi’ or ‘Masa’ or ‘Grammy’ depending on who she was to you, in February 2016, thanks to one of my roommates at the time, the sweetest boy from LA named Jonathan. We lived in this big house full of big characters in East London, and despite Jonathan and me having never met before, we quickly became close through being forced to share one bathroom between the 5 of us. While living together one winter, I went to LA for a modelling job and mentioned to him that I was yearning to stay longer but that I needed somewhere to stay.

“You should stay with my Grammy,” he suggested.

Considering my penchant for cross-generational friendships, this sounded like heaven, so I took him up on it!

After finishing my job, I headed to Viola’s directly from the set with my suitcase in an Uber, not knowing how this visit would impact my life forever. I pulled up to her beautiful mid-century American ranch-style home in Silverlake, the neighbourhood she has been a resident in for almost six decades — way before anyone could have imagined it’s evolution into what it is today — and there she was, this petite Japanese woman, waving to me in her cute jeans and a bright peach LL Bean sweater, adorned with the sweetest smile on her face. Even though we had never met, I couldn’t deny that there was something so utterly familiar about her to me. She gave me a small, shy hug, and I followed her into the house, where she swiftly showed me to my delightful room, and just like that, I was home.

Over the next 10 days, we rarely stopped talking. She brought me into her rich inner and outer worlds, where her everyday and mundane were some of the greatest moments of my life. Going to the laundromat together, Qi Gong at the Senior Center, browsing the new hardcover books at Barnes and Noble, chatting with everyone who worked at the Gelson’s market on Sunset, and dim-sum lunches with her Asian golden gal cousins and siblings-in-law at Din Tai Fung. To this day, some of the latest nights I’ve had in this city have been with Viola. We stayed up, having TCM marathons and inhaling three classic golden age-old Hollywood movies back-to-back until the early hours. The mornings at the house held such a magical, ethereal quality. The California sun would drench the front rooms with such gorgeous light, and we would sit out on the back patio, drinking coffee while we eagerly awaited the hummingbirds to make an appearance to sip nectar from her giant red hibiscus bush, always leaving me filled with awe to carry me through the day.

(her hibiscus bush on the back patio, with the hummingbird feeders I bought her many moons ago)

Los Angeles is famously isolating. Not only because of its sheer size and how it has been architecturally designed to separate people, but I’ve also found that this sense of isolation is caused by its transactional core, created by the magnified sense of capitalism here, where every little thing is monetized. Viola became the sturdy tree that helped me ground and grow roots of care, connection, and a sense of family in this strange city. After that first trip, we stayed close through phone calls, letters and book exchanges, and over the years I came to visit her as much as I could. Coming back to LA meant coming home to her, and this house that became a cocoon of love and family for me. Over time, she started telling people I was her granddaughter. Hearing this, my entire body would fizz in delight, making me feel whole in a way that I never knew I yearned for.

The magical thing was that Viola could've genetically been my grandmother, being of both Japanese and Okinawan descent. It was fascinating to notice how some inherent things about her felt so Japanese, from external things like her making okayu (Japanese rice porridge) for breakfast or more internal processes like hiding her harder emotions. Being born and raised in California, she was also the ‘perfect’ American homemaker, so much so that when it came to carving out a career for herself, she became a Home Economics teacher in different high schools in the LA school district. Through her students and the schools themselves (depending on which neighbourhood they were in) she had unique windows into what she described as the world of ‘haves and have-nots’. She spent many years teaching at schools in ‘underserved’ communities, where the student body was mostly made up of inner-city kids from immigrant backgrounds, often from families who had literally just arrived in America.

She would tell me how her classes became this important haven where students could come, even if they didn’t speak English, to use their senses and learn how to cook, sew, and take care of themselves in ways that many didn’t know how. It would make her sad to know that for some students, the meal they would cook in class would be their only meal that day, but she loved seeing how many of them would gain this new sense of autonomy from the skills they learned with her. She always spoke fondly of these experiences. Despite her job being emotionally arduous, her students opened her up to so many worlds and cultures she had known nothing about, and she always loved bumping into one of her old students somewhere all grown up with many stories of their own to share.

(Viola's sewing machine and work table in her home studio)

In touching on the moments that shaped her life, there is a dark but important chapter in Vi’s story, one that has often been purposely erased from history books that feels extra relevant to share in these times. Growing up on the West Coast of the United States in the 1940s meant she and her family fell victim to Executive Order 9066 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942, after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. Fueled by racism, xenophobia, and wartime hysteria, she and her family were subsequently sent to Poston, a Japanese internment camp in Arizona, for 2 years, alongside over 17,000 other members of the Japanese community.

Her memories of the camp are vague and hazy, as she was only three years old when they first arrived there, but she remembers how families lived in giant barracks all together, with nothing but a sheet or sometimes a plank of wood between them. She recounts how once in a blue moon they would watch movies, and in the films, she would be fascinated by people drinking from water fountains. Having access to water was so far removed from her reality that it became a dream that she fixated on. She said that camp is where she quickly learned about the Japanese concept of ‘gaman’, which in English roughly translates to a practice of resilience - that to survive in life: one had to suck it up and get on with it.

(Viola as a baby with her mother Tsuruko Nakamura at camp in Arizona, 1942)

She and her family survived and, via a rehousing camp, eventually ended up in Downtown LA with $20 to their name, living in a hotel that was owned by some friends of friends. They had lost everything they had before the war: a family home, a thriving business, and their dignity and like many other Japanese Americans, they were forced to start all over again. She shared with me one of her earliest memories from this time, living downtown, starting kindergarten for the first time, she and her cousin Yuriko had to walk to school together, but since for most of their cognisant life they had lived in a dusty barrack in the desert with no roads, they had no idea how to cross the street. They would stand in front of the lights downtown arguing back and forth over what the traffic lights meant, which made them late for school.

(Viola + and her cousin Yuriko as children when they first got out of camp)

(the last photo I took of Viola + Yuriko together in January 2023)

I asked Viola once if she felt angry at this country for what had happened to them. She said she didn’t feel anger for herself but that she did for her parents. She might not have been able to voice her anger then, but as an act of love, I voice my anger now. Today marks the Day of Remembrance of the signing of Executive Order 9066. As US citizens, these camps violated the constitutional rights of over 120,000 Japanese Americans, who were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in detention centres without due process.

They targeted individuals solely based on their Japanese ancestry, regardless of their loyalty or contributions to the country. During this time, in Viola’s motherland of Okinawa, (originally named the Ryukyu Islands pre-Japanese occupation) they experienced one of the most violent battles ever to be recorded, the Battle of Okinawa that killed over 100,000 men women and children, a quarter of the population in two months and led to the US occupation of Okinawa, which was official for the following 27 years, but to this day the ongoing military presence has ravaged the island and its people. In this time that we as a collective are witnessing the multiple genocidal entanglements by the classic empirical methods of displacement, dehumanisation and murder of Palestinians it feels important to keep making connections between all genocides and occupations, to hold the violence of the past and how it echoes in the violence of the present because ‘never again’ is happening now.

This is what America does, and at its core, since its inception, this is what America is and has always been.

(a photo of the Nakamura family pre-internment in Brawley, California 1941)

Like many older people, COVID really impacted Viola’s quality of life, which never returned to what it once was, because since she already had a pre-existing lung condition, she was always at risk. On the last few trips I made to see her, there was an understandable edge that my presence caused. No matter how careful I was or how often I tested, having to fly here etc, made me a risk to her. She ended up contracting COVID last summer and that was the beginning of the end. I was told in December last year that her health was deteriorating and that if I wanted to come and see her one last time, I should come soon, I booked my ticket immediately.

(Viola's bedroom)

In mid-January, 10 days before I was due to arrive in California, I received a sudden phone call from Jonathan who told me that Viola was in the hospital and was told by the doctors that her organs were shutting down, that she was too frail to recover and she could leave us any minute. I heard the words from his mouth and went into a state of shock. One of the first feelings that came up was an immense feeling of guilt because I had been going through so much of my own turmoil in the last few months that we had barely spoken. The next day, her eldest daughter and, by default, my honorary Aunt Stacey, helped facilitate a call from the hospital so I could say my final goodbye.

Through a river of tears, I told her how much I valued her presence in my life. I apologised for not being around the last few months and asked her for forgiveness. I thanked her for being a grandmother to me, a true friend, and a wonderful confidante, and I felt that her kinship meant the world to me. I love her eternally and wish her a safe passage to the next realm, and I look forward to the moment we reunite in whatever capacity, whenever possible. Even though she couldn’t speak back, her daughters there with her said they knew she could hear me as her breath began to pick up again. Her physical body left this realm swiftly and peacefully only a mere few hours later.

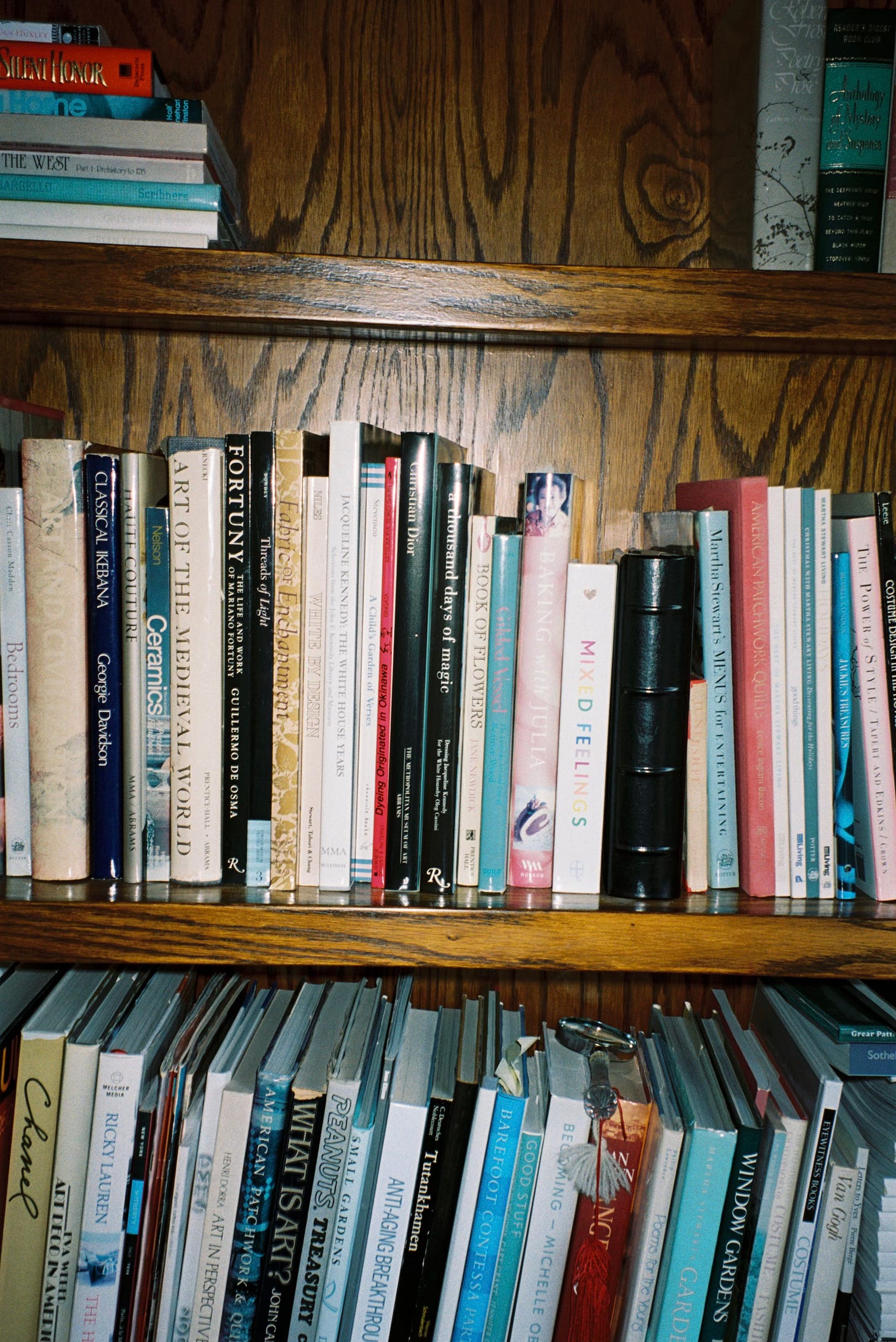

I am now writing these words from her house at the kitchen table where we shared so much life. Being here, in a time where we are seeing so many people unjustly killed who have not been able to have a dignified end-of-life ritual, I am reminded of what an honour it is to be in a person's personal space right after they’ve transitioned. The house is just as she left it. Her pantry is still full. Her crochet is still in the basket next to her chair, which had become known as ‘her office’ in the last few months when her health and mobility had declined. Squashed between the books on the bookshelf next to her chair is a Ziploc bag with cosmetics that she still liked to use, as she was never seen without a hair out of place.

The house is alive with her spirit. It smells like her, and I feel like she’s just about to walk through the door any second. I talk to her out loud, fill her in with what's been happening in my life, ask her her opinion, laugh, and tell her how my day was. I asked her to visit me in my dreams. Perhaps this is it; her physical body may no longer be here, but our bond has just evolved as she moves into the realm of guides and ancestors. I am relishing my moments here, soaking it all up, while trying to archive the house as she left it the best way I can by photographing all the little things because it will be the last time I see it like this.

(Viola's dining table, chair adorned with her crochet phone case she made for herself)

These days, I find myself turning to the legacies and wisdom of elders and teachers who have passed as I try to navigate the tumultuous waves of our time. I am contemplating the richness and utter solace and inspiration they’ve brought and continue to bring to my life. Under capitalism, older people in Western society tend to be rendered ‘futile’, and the pandemic only reminded us how little this system cares for or values them. I’ve lost all my grandmothers in the last 5 years, meaning my real-life elders are almost all gone. Even though, with Vi, I got to have this other kind of relationship than I did with my biological grandmothers. Living not just in different countries but on other continents away from my grandmothers growing up, I didn’t get nearly as much time as I wanted with either of them before they both passed away. Viola became my opportunity for a do-over, a chance to have the cross-generational friendship and intimacy I had yearned for from my blood that I never really got to experience in my adult life.

She was of many worlds.

And so was I.

Even though our situations and positionalities were nuanced—ie. Only one of my parents is Japanese. I was born in Japan, and I speak Japanese, albeit only conversationally. I racially read mixed or ambiguous, neither European nor super Asian. She was born and raised solely in California to one Japanese and one Okinawan parent, never went to either of her parents' homelands, didn’t speak the language due to forced assimilation and is visibly Asian. We both grew up as ‘outsiders’ even in the places we considered ‘home’, constantly being asked where we were from or complimented for our native language skills, somehow always both not quite ‘enough’ to appease our different sides.

But somehow, with Vi, despite our differences, I felt more whole.

(Viola in Los Angeles, some time in the 1960's)

There is something so precious about the closeness and intimacy one can share when family is chosen and not related by blood. My relationship with Vi has only reminded me that making and nurturing these relationships with our non-relational kin is also how we build new worlds across our differences. Like all humans, Viola’s story was big and complex, full of loss and love. What a gift that she trusted me enough to let me in and enrich my life with her stories, her heartaches, and moments of turning that allowed us to explore the depths of our shared humanity.

As I sit and invite in the many layers of grief and loss that are present in both my life and the larger collective, I’m also reminded that there is also something specific about this time after death where we are more open to the invisible world. We look for signs and take them as truth to comfort us in a time of transition. There is a precious window where our rational minds can take a break, and we are happy to accept mystery as our consensus reality. I’m hoping to stay in this dreamtime.

As I sat outside on the patio yesterday morning, on the exact chairs where we had spent those many mornings drinking coffee and lovingly admiring the many hummingbirds who came to feed in her beautiful red hibiscus bush, suddenly one appeared and started to sing its beautiful song to me. Once again, that mysterious familiarity I felt when I first met Vi hung in the air.

‘Why hello Vi’, I sang back.

Omg Naomi. What have we done to deserve you. This piece fed me where I didn't know I was hungry. What a gorgeous retelling of a beautiful relationship and a complicated history. Tears ran down my face as I sat at my work place desk chair. Thank you so much. I'm sure Jonathan will be so grateful to you for capturing this side of his Grammy.

With so much heaviness in the world and on our feeds, your heartfelt writing meant more to me now than ever. Thank you x

Hello Naiomi-chan, I hope you are staying well and finding enjoyment in daily life wherever your path has led you.

I wanted to thank you for all your work, but especially for sharing the story of your relationship with Viola. I grew up in an area in Los Angeles (a little ways away from Viola’s home in Silver Lake) where there was a sizable Japanese American community. Many of my friends’ parents had similar life stories as you described Viola’s family history.

I am grateful to you for sharing your adoptive Grandmother with us and for the warm flood of nostalgia that I felt personally…and I am thankful FOR YOU and your beaming strength of character and courage to speak your truth always and shine a light on all the injustice, exploitation and blatant persecution permeating our world today.

Thanks very much for all that you do. You are well appreciated each and every day!