34. songs for (and from) my father

transmissions through time, memory and the space in between

When people ask me if I remember my father, I close my eyes and all I hear is music.

I was eight years old when he passed away.

Now, when I see children who are eight, they look so small, so new, and it makes me realise how young I truly was. At that age, we’re only just beginning to store life in long-term memory, still learning to hold time in sequence. The trauma of his passing fractured that.

My siblings often ask if I remember more than they do, or they assume I must because I’m older than they are. But I don’t know. It touched each of us differently and shaped us in ways we’re still uncovering. What I remember most, lives in sound, not his voice, but the music that always surrounded him, that then surrounded us — like the trembling bass under my little feet on the tatami mat floor in our tiny Japanese home.

I recently came across a line from Alice Walker in an essay where she was writing about her father. She wrote, “I find that writing about people helps us to understand them better, and understanding them better helps us to accept them as part of ourselves. Since I share so many of my father’s characteristics, physical and otherwise, coming to terms with what he has meant to my life is crucial to a full acceptance. Acceptance and love of myself.” I think about that a lot, especially growing up without him, trying to understand someone who shaped me, even in his absence. I know I often reference him in my writing, but I don’t think I’ve ever really shared that much about him, beyond the fact that he passed away and that he was my father. It felt like something I wanted to do, to open that door a little wider.

My father’s name was Tsutomu Shimada. Born in Tokyo, he was the youngest of four. He carried joy like the sun. Many were drawn to his warmth, his big smile, and his openness. He moved through the world in a way that felt generous and so very alive.

In the early 1980s, he transformed my grandparents’ tiny porcelain and tea shop, which they started after the war, into one of Tokyo’s first vintage clothing stores, Beatniks. Within its tiny 15 m² walls, the shop was stuffed with an array of all things ‘Americana’: old denim, band merchandise, cowboy boots, jewellery made by Indigenous Americans, and, of course, records. It was tucked beneath the train tracks of the old Ameyoko Market near Ueno Station, in one of those tiny corridors lined with every kind of vendor.

Parts of the market were organised into sections, and one close to my father’s store primarily sold fish. Writing this reminds me that, even though I grew up between Spain and Japan — arguably two of the most fish-fanatic countries in the world — I didn’t eat fish until I was a late teenager. So much of the tuna and other fish eaten in Japan is actually sourced from Spain, and the relationship between the two countries with fish is deep and inextricable. For far too long, I associated the smell of fish with how it would taste, and I was completely averse to it. When I passed the section near my father’s store, I would insist on walking past with my fingers pinched over my nose, yelling “kusai!” (That stinks!). I’ve felt embarrassed about that for a long time, like, silly girl, come on!!!! You didn’t know what you were missing!!!!!

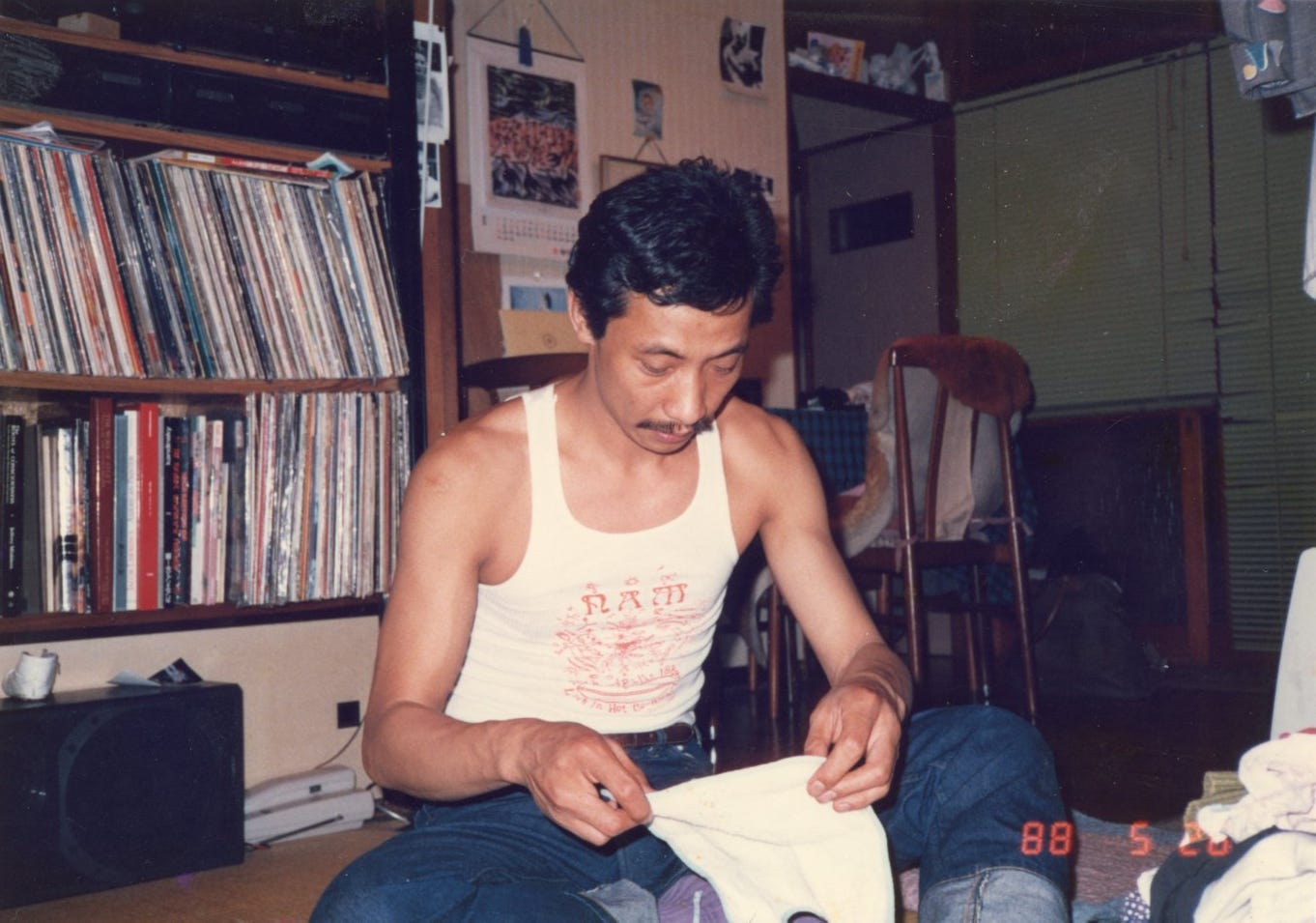

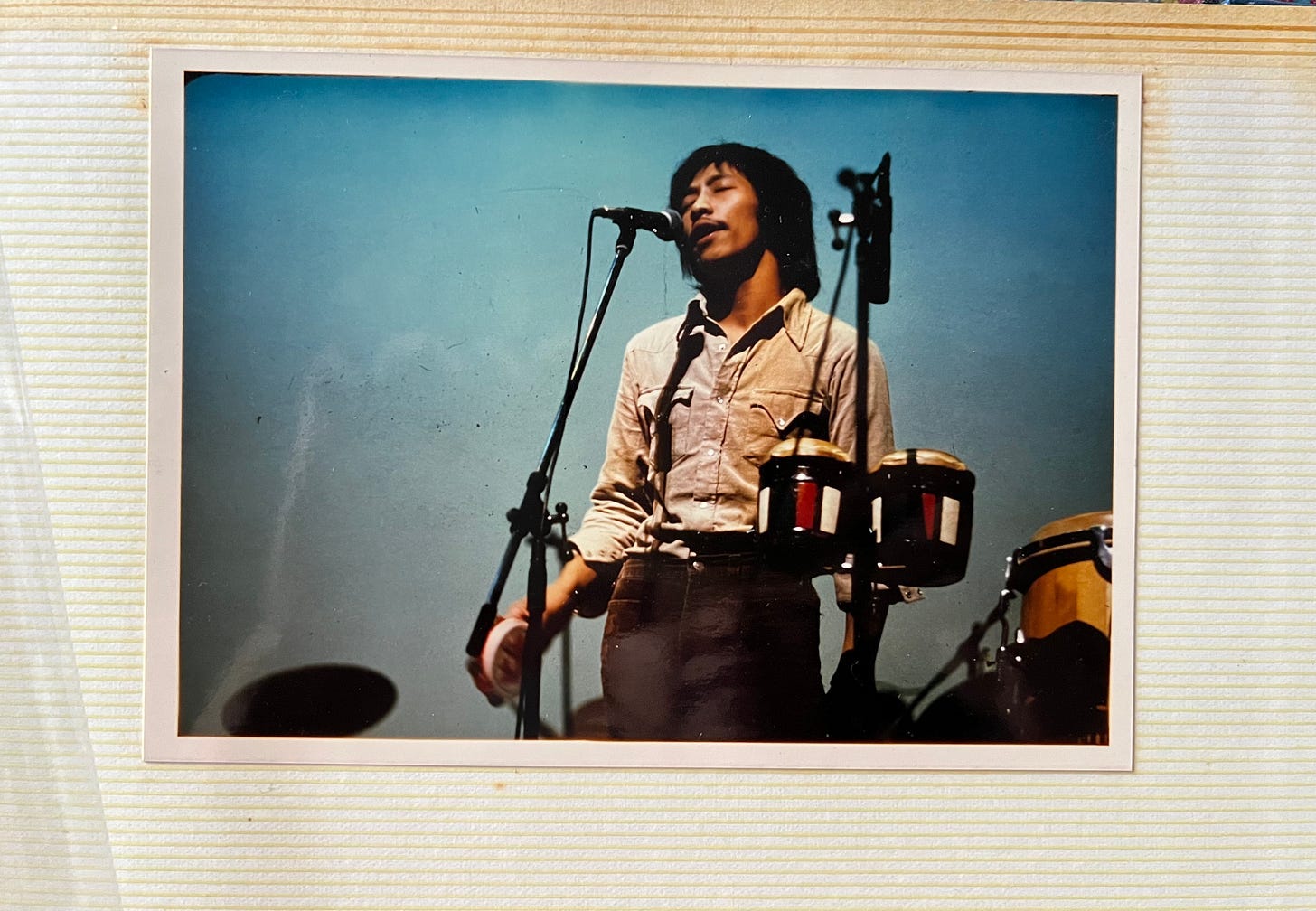

My father always loved music. He was an avid record collector, a deep listener. He loved and respected Black music deeply: R&B, roots, gospel, blues, reggae, and jazz lit up our home. The genres he loved weren’t created just for entertainment, they were born from refusal, and I think, in his quiet way, he recognised that. He didn’t live the life expected of a traditional Japanese man. At some point, he even formed a reggae-ish band called NAM with friends. He sang and played percussion, all kinds of pan. It exemplified how he resisted the roles and silences imposed upon him. While he made the best of it, I imagine that came with its struggles, too.

Even in the first traditional house we lived in when I was born, where my parents couldn’t stand up straight because the ceilings were too low and all of us slept in the same room, even in that tiny squeeze, there was sometimes a drum kit setup — what a sight and sound to behold! My parents' friends would come over, drink, and have jam sessions late into the night. There are photos of me sitting in the middle with my hands clapping in absolute delight.

I often think about how much of him remains. When he died, he left behind more than memory. Some of it lives in our bodies. My little brother Taro was only three when our father died, and yet they share mannerisms so specific it feels impossible to call it a coincidence. Their gestures, voices and ways of moving through the world are so alike. I see him in all of us, each carrying something different. I often wonder what is inherited through presence alone, what lingers without explanation, what adds to the many mysteries of life we’ll never fully understand.

And it’s not just in the physical. I often wonder if some of the music I’m drawn to isn’t just a matter of preference but a kind of invisible influence from him and our other ancestors, still shaping us not only as a means of communication, but as if they somehow know what is good for us. When I finally gained access to his vinyl collection, stored away for decades after he passed, I was struck by how many of the records were the same as those in my own collection, albums I’d loved without knowing he’d loved them too. It made me wonder if it was simply a matter of taste or something more profound.

Sometimes I hear a song and I feel like I’ve always known it, as if a part of me is speaking through it. My devotion to music, my orientation toward sound, is a way we stay close to each other, how I’ve learned to live with his absence and somehow continue our conversation. There are also songs that make me think of my father that I couldn’t listen to for years. They felt too sharp, too close. I was afraid they would split something wide open in me. And they did, some still do. But eventually, I let them in, and music became a way not only to make space for the ache but also to have an ongoing relationship with it. To meet grief more gently. To let it move inside me, through me. To dance with it.

He was diagnosed with malignant pleural mesothelioma from long-term asbestos exposure (that lined the train tracks over the markets where he worked), just before his 41st birthday and died five months later. We had just returned from a summer in British Columbia, Canada, surrounded by nature, where he’d been planning to move us. A lot of the vintage trading business was centred on the West Coast of the US and Canada, and since my mom was a Canadian citizen, it made sense. It was as if he already knew his life was becoming unsustainable, as if he could feel something was killing him.

Soon after our return, he collapsed, and as soon as they admitted him to the hospital, they said the cancer had already spread throughout his body. That it was terminal and there was nothing they could do. It was all too late. They now understand that he and my grandfather (his father, who passed away before I was born) both died from the same cancer, from the same kind of toxic exposure.

There is still so much I don’t know about him, and so much I never will. He will always remain partially shrouded in mystery. When I asked my mom to fill in some gaps about him, she often reminded me, “Naomi, we fell in love so quickly. We had you right away. Then, more children. It all happened so fast. There’s so much about your father I never got to know, or that he didn’t want to share with me. Then he just died. You never expect to have three kids alone.”

She said he was deeply loving, but also very private. Unarguably an outlier for his time, he was still, underneath it all, a Japanese man of his generation. Stubborn or ishi-atama (that translates to something like stone-head), as they would say in Japanese, and far from comfortable with vulnerability, so much so that he forbade my mother from letting any of us kids come to the hospital to visit.

One of the most painful things, according to my mom, was his avoidance. That he must’ve been sick for a long time and not done anything about it, and that even when all signs pointed to the fact that he was dying, he hands down refused to talk about it. They couldn’t make plans for his aftercare, funeral and for our future that he wasn’t going to be in. Whenever I think about this, tears come to my eyes. How lonely it must’ve been for her.

Sometimes, I try to piece things together: bits of stories, old photos, fragments that don’t quite form a whole. For example, I recently found a picture of the famous country singer Bonnie Raitt (photo below) at his store, and then another, later, backstage with her band. I don’t know the full story, and I wish I did!

In some ways, I’ve been constructing him my whole life. Rebuilding him through photographs, songs, the small crumbs of what some of the few people who knew him that I’m still in touch with have told me, and through what they haven’t. Photos so often capture the highlights, but I never really got to see the rest. I never witnessed the contradictions, the moodiness, the small imperfections that make someone whole. When you lose a parent young, you don’t get to grow alongside them, to notice how they change, or to meet them again in different seasons of your own life. You don’t get to know them in their full human-ness. And so they stay somewhat suspended in a golden kind of light, remembered through a Kodak lens. Beloved, idealised and unfinished. And yet these songs bring me closer to something, the ache of what I’ll never fully know, the mystery that lives inside love, the mystery that lives inside life.

One of my clearest memories of him — maybe only one of the few where I see him in motion — is of us together in our old forest green Nissan Prairie. My sister, Luka, my brother, Taro, and I packed into the back seat. The sunroof was open, and wind poured in from above; UB40 played loudly on the stereo. I called out, “Papa, play Rats in the Kitchen,” and he smiled, turned it up, and started drumming on the steering wheel. The whole car turned into a kind of sound system. That memory is so precious to me.

People often joke that Japanese people get a pass when it comes to cultural appropriation because they approach it with such reverence, such care, such fandom. But all jokes aside, I would have loved to have had that conversation with him (along with so many others). Just to hear how he thought about it. To ask him what it meant to move through the world so shaped by cultures not his own. Where admiration ends and appropriation begins. Where he saw himself inside that tension, or if he did at all. But maybe we’re having that conversation now, in this way.

And I suppose that circles back to what Alice Walker wrote. Since she shared so many of her father’s characteristics, coming to terms with what he meant to her life was essential to fully accepting herself. I think about that all the time. Because I do see him in me — his gestures, his obsessions, his appetite for sound. And like him, I’ve been shaped by many cultures that are not my own. I’ve moved through the world in ways I didn’t always choose. Places I didn’t always stay. And sometimes, I wonder where that puts me, too. But maybe that’s what I’m doing here — with these words, with these songs: trying to understand him better, trying to understand myself.

I’ve been hosting a monthly radio show, also named Tender Contributions, for the past five years on Foundation FM in London. The shows are a sonic archive of each moment in time, an ongoing mixtape of my life, often reflecting what’s happening in the world and my response to it. It has become an extended space for this tender universe. This year marked 29 years since my father passed, and on that anniversary, I finally made the show I’d been thinking about doing for a long time: a mix of songs that remind me of him. Songs that feel like messages. Not just nostalgia, but something still alive. A way of saying: I remember you, I hear you, I’m still listening. Also, because these songs are, in a way, my own origin story, they mark the beginning of my love for music. I wanted to share him, and them, with you.

You can listen to the original show here or follow the playlist here.

The tracklist:

1. Marvin Gaye – “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)”

What’s Going On was played constantly in our home. I think of it as part of my father’s internal landscape — grief, resistance and tenderness. I never got to discuss resistance movements or politics, but listening to his records makes me want to believe he felt it - that there was a deep respect for the oppressed, the struggle, and the spirit behind it.

2. Sweet Honey in the Rock – “We Are the Ones”

He had so many Sweet Honey in the Rock records. We Are the Ones — named after the June Jordan poem — is just pure joyous fire in the belly. I so wish I could ask him why he loved them so much, and if he had ever heard Jordan’s original poem.

3. Tuck & Patti – “Time After Time”

4. Tuck & Patti – “Dream”

Tuck & Patti’s music was playing a lot in our home toward the end of his life. Time After Time, with its soft ache, reminds me of that period. There’s something about their sound, ethereal, tender, and longing, that feels like a prelude to a goodbye, which makes it all the more bittersweet to listen. My parents had tickets to see them, but by the time the show came around, he was too sick to go. My mother went without him. That still breaks something in me.

5. Minnie Riperton - “Lovin’ You”

6. Minnie Riperton and Peabo Bryson - “Here We Go”

Like father, like daughter. He just adored the glorious Minnie Riperton, had every one of her albums, and so do I.

7. Bonnie Raitt - “Thank You”

See the story above!

8. Steely Dan - “Do It Again”

This song wasn’t in the original radio show; it’s something that’s only come back to me recently, and I felt like I just had to include it. When I came across his records decades later, I found every Steely Dan album in his collection; he was obviously a fan. I had never really resonated with them, but finding them gave me a chance to listen differently, to try again, to connect merely because he loved them. This is the track where I thought, maybe this can grow on me. So I added it to the playlist version, because it belongs.

9. Third World – “Now That We’ve Found Love”

This reminds me of him so much. We used to play it in the house all the time; it’s just him all over.

10. Bob Marley & The Wailers – “High Tide or Low Tide”

My father loved Bob Marley so much. He inspired him in a significant way, not just musically, but also ideologically and stylistically. I’ve sometimes felt hesitant to name Bob Marley because of how his culture has been overexposed and commodified, with his music reduced to something decorative or easily consumed, but he was a true mystic; his songs convey a kind of healing frequency that resonates beyond language. Marley was 36 when he died. My father was 41. I haven’t fully unpacked that parallel, but it’s there, I guess, something about what gets left behind, and what still carries.

11. Toots & The Maytals – “Pressure Drop”

We had a jungle gym inside our tiny kitchen. I used to hold onto the bars and bounce up and down to this song. My parents would literally climb through the jungle gym just to get to the sink to wash the dishes. It was so silly! It says a lot about them, and I love them for encouraging that kind of beautiful ridiculousness.

12. Dennis Brown – “Revolution”

This was also not in the original radio show; it was an afterthought. It’s a song I knew needed to be here. Resistance music has been such a big part of my own life and study, and this one ties the threads together. Did I choose it, or was it brought to me? Either way, this track is part of the legacy.

13. UB40 – “Rat in Mi Kitchen”

I can still hear his smile. This was our family song. Catchy, funny and full of sunshine and joy. We all still remember it as that. It was such an integral part of our childhood soundtrack.

14. Yui Yui Sisters – “Inishiri Bushi”

This was played at his funeral. I couldn’t listen to it for years. He was listening to a lot of Ryukyuan music near the end. It’s traditional music from Okinawa, before Japan colonised it. I wonder if it gave him comfort, even if he didn’t want to speak about dying, maybe the music helped him prepare for the oncoming.

Working on this piece, I realised I didn’t actually know the final details of how he left this Earth. Last night, I asked my mother for the first time. She told me they received a call from the hospital in the early evening: he likely wouldn’t make it through the night. Since we weren’t allowed in the hospital, she left us at home with a family friend and went to be by his side. Around his bed, a small circle formed — my mother, a few family members and close friends. Some he had grown up with, some he played music with. There were about ten of them in all. They held hands and sang his favourite songs, softly, a cappella. She said as he took his last breaths, held in song, he was smiling. That he looked at peace. That he drifted gently—not alone, but surrounded—into wherever it is we go next.

This is a small offering to you, Papa. A form of love passed through sound. A soundtrack of legacy, memory, inheritance and mystery. Miss you, Papa.

And thank you, all of you, for reading, for listening, for being here.

Thank you for this gift ❤️

Naomi <3 thank you